Women’s Brigade

Ten working women pose for the photographer. They range in age from sixteen to sixty and each holds a garment in their hands. There are two Singer sewing machines being operated by foot treadle, and a dress cloth on the silver plate. On the work table, a tough corset material rests on a pile of small jobs requiring hand stitching. All women are sewing garments, the main central figure holds a man’s serge jacket and buttonholer. The two men in the picture are almost invisible, one slight well-dressed floor man and another entering from the back room. Wicker baskets along the shelves collect and return orders. This is an industrial scene. In 1903, the Broken Hill tailoresses formed a trade union and held a stall at the ‘Barrier Daily Truth Fair’. One year later the Hotel Club and Caterers Union, led by Miss O’Donohue, called upon union solidarity to support their claims. Their union Secretary, Miss Plummer, spoke at Mass Meetings and called upon women to refuse to be served in shops by non-unionists. The Shop Assistants Union, composed predominantly of young women, called for a boycott of all ‘Scab’ shops. Women were political and radically active from the earliest days of the Women’s Brigade which formed in 1889. This was the year that Mary Jane Cameron, the young assistant teacher from Silverton Public School who had been radicalised by the Socialist movement, left to join William Lane’s Socialist Utopia in Paraguay. Although many women found their voice in Charitable and Friendly Societies, their organising abilities and public speaking should not be considered as secondary to the role of men in the Industrial disputes that mark Broken Hill’s history. As early as 1892, women held a mass rally on the Central Reserve to call for ‘Freedom of Speech’. Mrs Rogers addressed the crowd and expressed the hope that ‘men and women alike would stand out so that in future their children might be able to boast that their parents had won the privilege they would enjoy.1’ During the strike of 1892, The Barrier United Females Strike Protest Committee took a petition, signed by women, to the Governor: Your petitioners regret that the present Constitution will not allow them a voice in framing the laws under which they are compelled to live… [we] appeal to the clemency and humanitarianness of your Excellency and his advisors to adopt all constitutional measures to allieviate your petitioner’s many woes and distresses which are caused by a handful of men in their determined and inhumane endeavour to force the iniquitous system of cut throat competitive contracting upon our fathers, brothers, husbands and sweethearts2. After the miners were unsuccessful in preventing contract stopping and gaining a 46 hour week, families were punished by the Mining Companies. Miners who had joined the union strike were blacklisted along the line of load for two years. Women who took in washing were hit financially by the water famine and typhoid raged. In 1895, infant mortality accounted for 50% of all deaths on the mining field. A.G. Hales, Mining Reporter, commented upon the fate of women on the Barrier Ranges. There are sick and weakly women in our midst who struggle on day by day with hard fare and hard work in little cabins, hot and dirty, slowly but surely sinking in to premature graves, doing their daily work patiently and bravely with the resolute courage the Australian woman alone possesses.3 The women did not remain in their little cabins. On November 12th 1889, amid the one week strike against non-union labour on the field, four hundred women met with A.G. Hales and Richard Sleath, President of the Miner’s Association at Taits Masonic Hall. After the President ‘preached to them the religion of extermination’, they formed the Women’s Brigade. Hales implored ‘the sisterhood of labour to stand for the men and not allow themselves to touch a thing owned by a ‘blackleg’. Then a pair of pretty girls, about eighteen summers in extent, arose and said they were single girls and sisters and they did not desire to do anything unladylike, but they were willing to “scat” the face of any blackleg in Broken Hill …Then Miss Zachariah Cliff arose and she tucked her skirt between her knees … she declared that sooner than she’d rear children to see them become blacklegs, she’d join the Anti-propagation Society4. The women went on that evening to tar and feather two ‘blacklegs’ they found in the town. The daughters marched with mops and brooms to ‘sweep the mines clean of blacklegs’5. The issues that arose in 1892 concerned the introduction of Contracts for miners on the stopes. It was feared this level of competition between mining teams would reduce wages and lead to the Companies cutting corners on safety to maximise productivity. On July 3rd 1892, Josiah Thomas of the AMA, addressed a mass meeting of 5000 men and women on the Central reserve, There is not one man or woman who does not regret, and deeply too, that the Directors had broken the agreement between themselves and the miners. 6 The strike began on July 4th with the establishment of Picket lines and the smashing of a truck taking whiskey, bread and tea to the blacklegs. Police Constables were brought to the city to control the crowds and non-union labour, tarred as ‘scabs’, were imported from Sydney by train. On August 25th, the Barrier United Females Strike Protest Committee mustered 500 volunteers to serve on the picket lines. There was a violent confrontation during which women used brooms and mops to attack the carriages and beat the imported labourers and police. Later that afternoon an additional 100 women joined them and they were applauded when they arrived at the Central Reserve to prepare for the AMA street procession. In addition to a speech by the AMA President, there were speeches made by five female orators. Mrs Rogers pointed out that the Contract System had brought misery to other parts of the Country.Dig deeper >

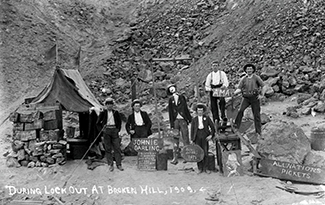

Lockout – Mock Grave for John Darling – January 1st, 1909

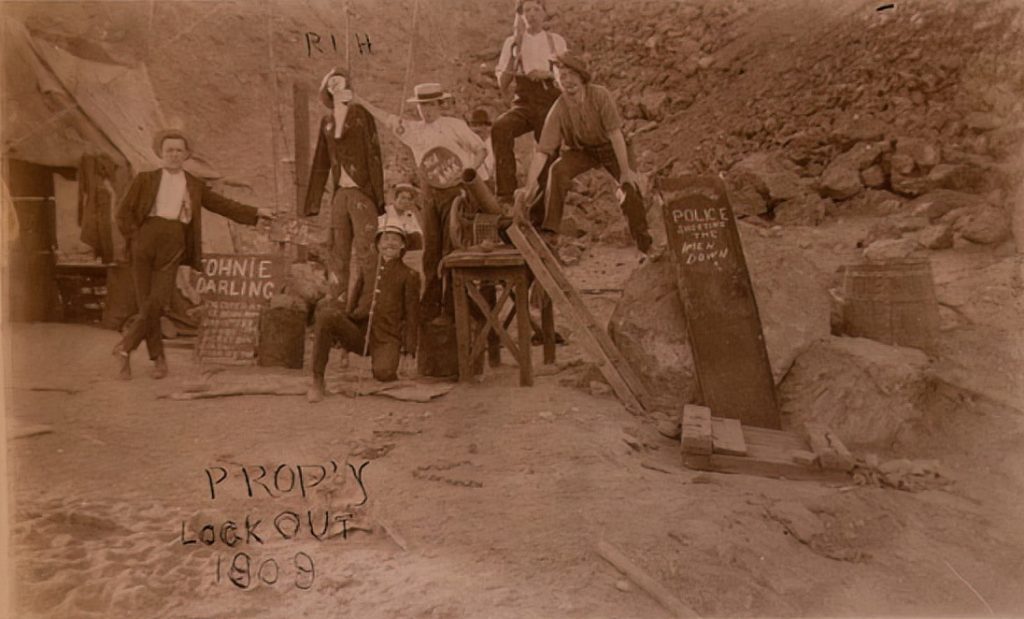

The Award for Miner’s wages and conditions established in 1906 expired on December 31st 1908. The Mining Manager’s Association held talks with the union representatives early in the month, but the Broken Hill Proprietary Company, Chaired by John Darling, and three other companies announced that due to low metal prices, they would discontinue the 12.5% increase in wages promised in 1906. A mass meeting of unionists working on the BHP, British, Junction and Block 10 Mines voted to stop work while seeking arbitration. The mines in question, ‘locked out’ all but essential workers. On January 1st the union picket lines were drawn and those who crossed the picket lines were accosted by union men and women. For the men on the picket lines, four hour shifts of standing and waiting weighed heavily upon them. The AMA established a wood yard, co-op store and bakery to relieve distress. Pickets were paid in monthly food coupons according to time spent on the lines. They made mock graves and held funerals to relieve the anger and powerlessness they felt. Mining Managers and Company Directors, such as John Darling of the Broken Hill Propriety Company, were often targeted. The mock graves and epitaphs were directed at union-breaking labourers including shift bosses, ‘black-legs’ and ‘scabs’1. Special Constables, brought in from Sydney, manned their own lines of defence, protecting the mine offices. Ironically, they constructed a mock grave for the visiting British Socialist, Tom Mann, who was rousing the unionists to solidarity and a class revolution. PHOTO 90/1/2653 “POLICEMEN ATA MOCK GRAVE FOR UNIONIST TOM MANN” Joseph Brokenshire, Photographer. Violence erupted on January 9th with a pitched street battle between police and union men. Many were injured including women and children. The newspaper decried the police as ‘cowardly women beaters’ with reports the police used some of the rebel women as human shields. It had been Tom Mann’s tactical and ‘new departure’ to request at the mass rally on January 8th, that women march at the head of the procession2. Twenty eight protesters, including Tom Mann, were incarcerated in the Broken Hill Gaol.

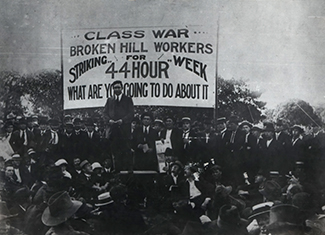

Addressing the Workers

Tom Mann the Social activist from Great Britain addressed the Women’s League on Wednesday 14th October, 1908 urging them to ‘resist any lowering of the standard of living on the Barrier, and calling upon the men to claim the half-holiday as a reasonable concession’ to their demands in the Award negotiations due for review in December. The crowds in the Trades Hall overflowed and he had to address a mixed audience and repeat his speech outside. You will note the number of children and families in attendance. His next speech on Monday October 19th, dealt with the importance of Industrial action to fight a Class war against the capitalist Mining Companies. The AMA invited Tom Mann and Lizzie Ahern to address a mass meeting at the outbreak of the strike. He delivered a speech on January 8th 1909 that incited women to lead the procession against the police and scabs the following day. A violent street battle ensued, during which Tom Mann and twenty seven male protesters were arrested. Thousands of townsfolk encamped around the gaol. Most of the protesters were acquitted or fined, some served short sentences. Tom Mann was released on a bond not to make speeches in New South Wales or assist the strikers. This lead him to deliver two speeches at Cockburn across the South Australian Border, which were attended by hundreds of citizens who boarded special ‘Picnic’ trains to and from the events. His ‘Open Letter to Trade unionists on Methods of Industrial Organisation’ was published by the Barrier Daily Truth in May 1909. He called for solidarity in the face of sectional interests. He saw a people disenchanted with politics and parliaments superseding the Capitalist order with a Federation of Unions, initiatives and referendums. He preached a Class revolution in which the new order would depend upon the intelligence of the worker. The Barrier Socialist group recognised the importance of education. In January 1908, at the Paris Commune celebrations, the socialist newspaper ‘The Flame’ called for women and children to be politically aware. They invited Tom Mann, the British trade union orator, to Broken Hill to found the Socialist Sunday School. Meetings were held at the Trades Hall and combined hymn singing with industrial union activism. It is important to note that Tom Mann went in to the British Coal Mines as a labourer at ten years of age. The earliest mines of the Barrier Ranges relied upon the labour of children as ‘picky boys’. Sunday was their day of rest and education. Tom Mann’s speeches to the Women’s movement in October 1908, connected local women with the international women’s movement for social reform. The Barrier Daily Truth ran a virulent women’s column with regular contributors who responded: ‘Why should the men fight the battle alone, while the children must eat bread and treacle to save the meat for the men who work underground?’ Tom Mann’s speech on, ‘The Social Upheaval, its causes and cure’ urged women to use their ‘influence’ to get their men to join the union. Unfortunately Union membership remained low and again the strike action was unsuccessful. On March 12th, Justice Higgins had ruled that the workers at Broken Hill and Port Pirie should return to work with no change to wages but hours reduced to 46 hours per week. The Broken Hill Propriety Company took the dispute to the High Court and clawed back the two hours per week concession. On May 19th , the miners agreed to return to work at pre-strike wages and hours. However, Broken Hill Proprietary Company did not resume underground operations. In addition to blackballing union strikers, they operated only surface workings treating the skimp dumps for two years. They turned toward other fields and diversified their interests. It was the beginning of the end of the ‘Big Mine’ in Broken Hill.

During lockout at Broken Hill 1909 – the effigy

Ill feeling toward the Broken Hill Proprietary Company ran high during the days when workers were locked out from the field. Since the NSW Arbitration Act of 1901, all negotiations had to be through the Courts. The following year BHP cut wages by 10% and two thousand miners left for other fields. In 1903, Justice Cohen refused to vary the 1893 agreement, freezing wages and introducing two-week contracts for underground workers. The town population dropped by 5,000 people. In 1906, the AMA elected by secret ballot to negotiate directly with Mr G.D. Delprat, General Manager of BHP. He attended the Trades Hall as a ‘private citizen’ and as a result the MMA and AMA agreed on the first wage rise in 13 years1. The 12.5% lead bonus would be paid until December 1908. By then the mineral prices had again plummeted and John Darling, the new head of BHP, refused to honour the previous agreement and withdrew from Arbitration. The miners regarded the dispute as a ‘Lock Out’, the MMA regarded it as a strike. The startling effigy of John Darling of the Broken Hill Propriety Company was not a first for the mining field. In the drought of 1888, only 9ml of rain fell across the district. Stephen’s Creek reservoir, the main source of water for the mines and townsfolk, dried up. In one ten day period there were forty seven cases of typhoid and enteric fever caused by drinking impure water from dams, wells and soaks. In September, the Minister for Mines, Mr Francis Abigail was charged with ‘criminal and cruel neglect of the inhabitants’ when he refused water to be taken from the Government owned Rat Hole Tank at Silverton. At four o’clock a hearse drawn by six horses and bearing the words “We will have Water”, paraded along Argent Street. It was led by a brass band playing the ‘Dead March’ and followed by a watercart, drawn by a dozen donkeys, bearing the sign ‘Empty’. It made its way past the overcrowded balcony of Aldridge’s Grand Hotel, and climbed the rise to the Central Reserve on Sulphide Street. Over six thousand people, gathered around a timber scaffold. ‘On the top there were several townsmen including Messrs. McCarthy and Edwards, Solicitors, and Mr Chapple … in their midst there was a splendid effigy of Mr. Abigail, seated in a black coffin with a rope around his neck and an empty waterbag in his hand…the effigy was saturated with kerosene, lighted and hoisted on the gallows. The noise made by the mob as the flames spread over the body was deafening. The effigy had been crammed full of fireworks of various descriptions, which exploded as the fire spread.’2 Mr Abigail rescinded his decision and water was transported from Silverton by train, then distributed by water carts across the town. This type of effective street theatre continued throughout the next three decades of industrial action. For more info etc – LINK TO THE MOCK GRAVES ETC

Silverton Picnic Day – April 20th 1908

On Easter Monday, a party of young men and women enjoy a picnic at Silverton. When the mines and sulphurous smelters of Broken Hill denuded the nearby hills of trees, the Silverton Tramway Company delivered day-trippers to the shady creeks at Penrose Park, Silverton and McCulloch Park, Tarrawingie. Little did these revellers imagine the stormy year which lay ahead for the families and miners working on the Broken Hill line of load. The original Picnic photograph, was described as ‘At the Rechabites’ Picnic’1. The Rechabites Lodge was a Friendly Society offering members assistance in times of hardship and illness and promoting total abstinence from alcohol. There were thirty seven Friendly Societies and Lodges operating in Broken Hill in 19082. These included the Manchester Unity Independent Order of Oddfellows. An accident had occurred at the MUIO picnic the year before this photograph was taken, when a young boy named Alick Pengelley wandered away and drowned in a nearby dam3. It was not the last time a Manchester Unity picnic would be marred by tragedy. On New Year’s Day, 1915, the Manchester Unity picnic train was the target of the first foreign attack on Australian soil during World War 1. Two disaffected men, Gool Mahomed and Mullah Abdullah, fired upon the open picnic carriages on the outskirts of Broken Hill. Seven people were wounded and six were killed including the two gunmen. Documents found at the site of the final shoot-out included Gool Mahomed’s application to enlist in the Turkish Army and a note in Urdu stating, ‘I kill your people because your people are fighting my country.’4 Learn more about this part of Broken Hill History at Sulphide St Museum etc. REFER TO SULPHIDE ST RAILWAY ETC Outback Museum Stories.

Life in the Early Days

The story of Broken Hill begins with the search for water. The Bulalli, Barkinji and Wilyakali river people, wandered the arid lands of what colonials later called Far Western New South Wales in search of food and water. Some tribes held ceremony and painted rock art in watering places such as Muttawintjie. They knew the location of soaks and creeks that to the naked European eye were merely hollows and stony beds. From 1850, the Darling River (Barka) supported Squatter’s cattle and sheep. Drovers kept moving west in search of new pasture and water. Bullock teams supplying the outstations and carting wool to and from South Australia, watered at the Thackaringa Dam. Unsurprisingly, the discovery of minerals was made by two well sinkers, Nickel and McLean. They plonked a lump of Galena on the bar of John Stokie’s grog shanty and he identified the first specimen of Silver-Lead ore on the Barrier Ranges. Another publican, Paddy Green of Menindee, pegged the claim as the Pioneer Mine in 18761. Three years later, John Stokie meandered on in his quest for water and beer, and established the Umberumberka store, advertising wine and spirit discounts for station hawkers. It was situated on flat land beside a shady creek the first nations people referred to as a native rat hole. In 1881, Stokie discovered silver and pegged his claim. The Umberumberka Mine gave rise to the first settlement of a store, a hotel and two boarding houses for miners. As the silver flowed more families settled and Silverton was incorporated as a municipality. Market gardens sprang up along the creek and supplied vegetables and dairy produce to the new field at the black ironstone outcrop described as ‘the broken hill’. It had been discovered by a German boundary rider, Charles Rasp, from Mount Gipps Station. The Silverton Tramway Company built a rail line to Cockburn on the South Australian Border and serviced many mining settlements of one to five hundred souls at Thackaringa, The Pinnacles, the Apollyon Valley, Nickelville, Albion Town, Taltingan on Round Hill, Mount Robe, Tarrawingee, Eurowie, Eaglehawk and Acacia Dam. A German community formed around Carltown , named after the German sly-grog pervayor German Charlie Carl. The more respectable brewers were the Resch brothers, Richard, Emil and Edmund, founders of the Lion Brewery. They were in business with the Mayor, John Penrose, an irrascible Yorkshire sailor who had come ashore in Sydney and followed the Rivers to Wilcannia where he set up as a publican and married Caroline Mitselberg. The couple then moved to the bonanza that was Silverton. They had eight daughters and John Penrose became the Mayor of Silverton. In 1884, a public meeting in Silverton formed the Barrier Miner’s Association a friendly society of the English model for the relief of miners who suffered injury. When fever came along and encamped upon the field for a spell, men lay down like wounded sheep to die, with no mother’s hand to soothe them, no sisters love to relieve their sufferings, and in many cases deserted by their mates.A.G.Hales, Wanderings of a Simple Child, 1890 The following year, a group of pastoral workers and local mineral speculators formed a syndicate called the Broken Hill Propriety Company Limited. The astounding value of their blocks elevated the hammer-and-tap dugouts to an industrial level of production. In January 1886, it was Big Jim Wilkinson, the Canadian Coach driver and mineral speculator, who presided over a public meeting to form a more radical union. The Amalgamated Miners’ Association of Australasia was formed on a Victorian model of agitation for miner’s rights and they adopted the motto, ‘United We Stand, divided we fall’. Meetings were held that week across the diggings at Silverton, Day Dream, Purnamoota and Broken Hill. Their eleven point agenda, including fair wages, compensation for injury, an eight hour day and a weekly recreation day, would take thirty four years of struggle to achieve. Culture thrived in Silverton on the strength of the silver slug: banks, a two storey De Baun’s Hotel; coach services, teamsters, miners, a hospital, four churches, Kidman’s Butcher shop, Dickens’ Pastoral Agency, municipal chambers, a literary society, brass band, school and the Silver Age newspaper. The first policeman, Richard O’Connell, fresh from the trail of Ned Kelly at Jerilderie, raised hell as the local policeman and retired to the genteel life of a publican. The shady creeks at Umberumberka and at Stephen’s Creek became recreation grounds for the population of miners, townsfolk and their families. The mines at Broken Hill, with sulphurous smelters and greedy wood-fired engines, soon denuded the surrounding country of trees. The dustbowl was blighted by water famine and drought. The green and shady Penrose Park and McCullum Park, were serviced by the Silverton Tramway Company which delivered day-trip passengers to Silverton and Tarrawingie. While the Penrose family home was being jinkered to Chapel Street, to serve as a Salvation Army home for unmarried mothers, the Resch Brothers moved to Melbourne, Sydney and Cootamundra. They established and grew the Lion, Resch and Carlton breweries in these cities. Mr Shelley, the Broken Hill cordial maker, also successfully exported his business to Sydney. The temperance movement, fostered by the high number of Cornish and Methodist residents, preferred cordials to beer. All were in need of a supply of fresh water. There are many photographs of Victorian ladies and their dapper beaus enjoying a bottle of cordial under a gum tree. Two invisible things were necessary for a picnic, leisure and wages. These formed the core of the miner’s demands and prompted their first refusal to work that occurred in 1889. They wanted a reduction in working hours and an increase in wages. The withholding of the only resource available to the workers, labour, would only work if their fellows agreed to stop work also. They had to be unified in their demands and sanctions. Or this reason, the non-unionist or ‘blackleg’ became the scourge of their lives. Solidarity was the only means of exerting power overDig deeper >

United we stand

The phrase, ‘United we stand: Divided we fall’ was adopted as the motto of the Amalgamated Miners’ Association of Australasia (AMA) which formed in Silverton in January 1886. Meetings were held that week across the diggings at Silverton, Daydream, Purnamoota and Broken Hill. Their eleven point agenda included fair wages, compensation for work-related injuries and illnesses, an eight hour day and a weekly recreation day. It would take the next thirty four years of struggle to achieve these conditions. The crucible of their success lay in the industrial strike action taken in 1909.

OUTBACK MUSEUMS Stories

The best way to experience Broken Hill history is to visit a local museum and get hands on with the amazing heritage the region has on display. Check out some of the best local museum experiences.

‘United We Stand’ Heritage Performance

In this entertaining short live show, you’re invited to step back in time to May 1919, and explore the city’s mining past as you join local actors in a ‘union meeting’ of the Amalgamated Miners Association (AMA), set on the eve of the strike action that changed Australia forever. Building on previous strikes, the ‘Great Strike’ saw the community work together in solidarity for 18 months between May 1919 and November 1920 to strike against unsafe working conditions and low wages in the Broken Hill silver mines. This action remains one of the hardest-fought industrial disputes this country has ever seen. The coordinated efforts by workers and their families paved the way for better pay, safer working conditions, and a workers compensation scheme for injured workers. These agreements formed the platform for our current national WHS and Compensation Acts, and contributed to Broken Hill being named Australia’s first Nationally Heritage Listed City in 2015. ‘United we stand’ tourist play was commissioned for the Indian Pacific off-train experiences by Journey Beyond, and has been seen by around 10,000 passengers since it’s inception in April 2017? The show has since been performed by an increasing number of local actors who have helped highlight this important part of our local and national heritage. The shows have now been performed in the community at events including the Broken Hill Heritage Festival ‘Heritage Highlighted’ event, Mundi Mundi Bash fringe in town square, and to open a concert in Trades Hall. In addition, the success of the show lead to a successful NSW Government Heritage Grant, ‘United We Stand: Strikes Scabs & Solidarity in Broken Hill’, which saw the concept expanded to include the development of props and costumes to produce Augmented Reality Postcards featuring recreations of the 1909 Lockout and early Picnic Days. For more information contact UWS@brokenhillhistory.com Download the script [LINK / download]View photo gallery [LINK to gallery]

Strikes, Scabs and Augmented Reality in Broken Hill

Postcards were the ‘Social Media’ of years gone by. See history come to life through the development of reproduction props, costumes, and Augmented Reality Postcards inspired by famous Broken Hill postcard photographs featuring short video clips produced locally for ‘United We Stand: Strikes Scabs and Solidarity in Broken Hill’. INSERT PIC OF one or two ACTUAL POSTCARDS OF GRAVES In the early years of Broken Hill, it was common for people to reproduce postcards to share with the community. This was done for a number of reasons. Some of the most famous examples of Broken Hill postcards were the images of mock graves and campsites captured and shared during the militant 1909 Lockout and early Picnic Days. In the lockout, Tom Mann famously unionised the workforce and helped convince the workers of BHP to strike for better wages. He then took the postcards to England to assist motivating workers to join the cause for solidarity in the labour movement there. Caption: some of the crew who helped bring history to life. Film shoot in Dec 2021. About the Project: Based on the successful United We Stand Tourist play, funding was secured for a NSW Government Heritage Grant to develop United We Stand: Strikes Scabs & Solidarity in Broken Hill, which included the development of props and costumes to produce Augmented Reality Postcards featuring recreations of several postcards from this period. The final postcards produced focussed on the early unionisation period of Broken Hill’s history and feature two postcards from the 1909 lockout and one of a picnic in a creek bed in 1908. In addition to recreating mock graves and costumes from the period, we were able to incorporate Augmented Reality experience to bring history to life. Th post cards are for sale at selected museums as a fundraising initiate to help these vital community resources. Check out ‘Outback Museum Stories’ to find out more about Broken Museum experiences. How it works: By scanning the QR code you can access the technology to hold a mobile device over the video to watch a video as the post card has come to life. Read on for examples of the postcards as well as the reference images and videos created. Picnic Day 1909 Lockout Effigy 1909 Lockout Mock Graves