Ten working women pose for the photographer. They range in age from sixteen to sixty and each holds a garment in their hands. There are two Singer sewing machines being operated by foot treadle, and a dress cloth on the silver plate. On the work table, a tough corset material rests on a pile of small jobs requiring hand stitching. All women are sewing garments, the main central figure holds a man’s serge jacket and buttonholer. The two men in the picture are almost invisible, one slight well-dressed floor man and another entering from the back room. Wicker baskets along the shelves collect and return orders. This is an industrial scene.

In 1903, the Broken Hill tailoresses formed a trade union and held a stall at the ‘Barrier Daily Truth Fair’. One year later the Hotel Club and Caterers Union, led by Miss O’Donohue, called upon union solidarity to support their claims. Their union Secretary, Miss Plummer, spoke at Mass Meetings and called upon women to refuse to be served in shops by non-unionists. The Shop Assistants Union, composed predominantly of young women, called for a boycott of all ‘Scab’ shops. Women were political and radically active from the earliest days of the Women’s Brigade which formed in 1889. This was the year that Mary Jane Cameron, the young assistant teacher from Silverton Public School who had been radicalised by the Socialist movement, left to join William Lane’s Socialist Utopia in Paraguay.

Although many women found their voice in Charitable and Friendly Societies, their organising abilities and public speaking should not be considered as secondary to the role of men in the Industrial disputes that mark Broken Hill’s history. As early as 1892, women held a mass rally on the Central Reserve to call for ‘Freedom of Speech’. Mrs Rogers addressed the crowd and expressed the hope that ‘men and women alike would stand out so that in future their children might be able to boast that their parents had won the privilege they would enjoy.1’

During the strike of 1892, The Barrier United Females Strike Protest Committee took a petition, signed by women, to the Governor:

Your petitioners regret that the present Constitution will not allow them a voice in framing the laws under which they are compelled to live… [we] appeal to the clemency and humanitarianness of your Excellency and his advisors to adopt all constitutional measures to allieviate your petitioner’s many woes and distresses which are caused by a handful of men in their determined and inhumane endeavour to force the iniquitous system of cut throat competitive contracting upon our fathers, brothers, husbands and sweethearts2.

After the miners were unsuccessful in preventing contract stopping and gaining a 46 hour week, families were punished by the Mining Companies. Miners who had joined the union strike were blacklisted along the line of load for two years. Women who took in washing were hit financially by the water famine and typhoid raged. In 1895, infant mortality accounted for 50% of all deaths on the mining field.

A.G. Hales, Mining Reporter, commented upon the fate of women on the Barrier Ranges.

There are sick and weakly women in our midst who struggle on day by day with hard fare and hard work in little cabins, hot and dirty, slowly but surely sinking in to premature graves, doing their daily work patiently and bravely with the resolute courage the Australian woman alone possesses.3

The women did not remain in their little cabins. On November 12th 1889, amid the one week strike against non-union labour on the field, four hundred women met with A.G. Hales and Richard Sleath, President of the Miner’s Association at Taits Masonic Hall. After the President ‘preached to them the religion of extermination’, they formed the Women’s Brigade. Hales implored ‘the sisterhood of labour to stand for the men and not allow themselves to touch a thing owned by a ‘blackleg’.

Then a pair of pretty girls, about eighteen summers in extent, arose and said they were single girls and sisters and they did not desire to do anything unladylike, but they were willing to “scat” the face of any blackleg in Broken Hill …Then Miss Zachariah Cliff arose and she tucked her skirt between her knees … she declared that sooner than she’d rear children to see them become blacklegs, she’d join the Anti-propagation Society4.

The women went on that evening to tar and feather two ‘blacklegs’ they found in the town. The daughters marched with mops and brooms to ‘sweep the mines clean of blacklegs’5.

The issues that arose in 1892 concerned the introduction of Contracts for miners on the stopes. It was feared this level of competition between mining teams would reduce wages and lead to the Companies cutting corners on safety to maximise productivity.

On July 3rd 1892, Josiah Thomas of the AMA, addressed a mass meeting of 5000 men and women on the Central reserve,

There is not one man or woman who does not regret, and deeply too, that the Directors had broken the agreement between themselves and the miners. 6

The strike began on July 4th with the establishment of Picket lines and the smashing of a truck taking whiskey, bread and tea to the blacklegs.

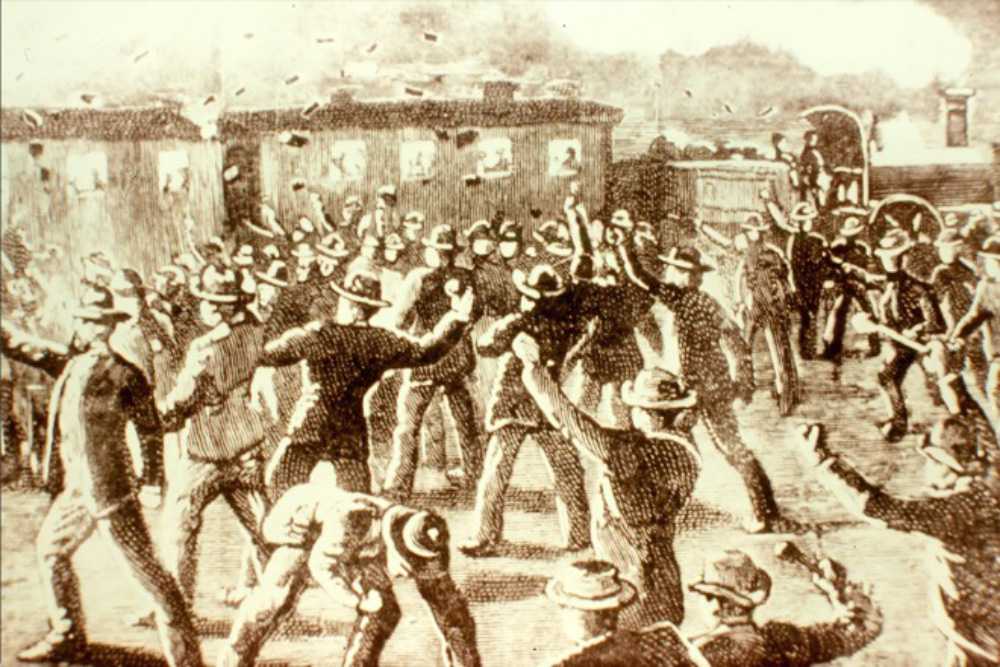

Police Constables were brought to the city to control the crowds and non-union labour, tarred as ‘scabs’, were imported from Sydney by train. On August 25th, the Barrier United Females Strike Protest Committee mustered 500 volunteers to serve on the picket lines. There was a violent confrontation during which women used brooms and mops to attack the carriages and beat the imported labourers and police.

Later that afternoon an additional 100 women joined them and they were applauded when they arrived at the Central Reserve to prepare for the AMA street procession. In addition to a speech by the AMA President, there were speeches made by five female orators.

Mrs Rogers pointed out that the Contract System had brought misery to other parts of the Country. In regard to a man who had attended the last women’s rally dressed in women’s clothing she said, ‘If the women caught him there again, they would see if they could make a woman of him.7

One and a half thousand spectators lined the streets as Mrs Poole, Field Marshall, and Mr Richard Sleath, President of the AMA, led a parade of 500 unionists marching to the tune of the AMA Brass band. However, union membership across the field remained low with only 2000 of the 5000 miners identified as unionists. The strike ended after five months of privation and Justice Cohen established an Award allowing contract mining and frozen wages. The miners who had taken part in the strike were blacklisted by all of the mining Companies along the line of load and their families suffered alongside them.

Two leading socialist women, Mrs Anderson and Miss Lizzy Ahern, who had been imprisoned for preaching Socialism on the streets of Prahran, were invited to address the Barrier Socialists in Broken Hill. The Barrier Miner reported that ‘the women clearly saw such struggles as their own interest and took pride in their own role in them, it was not a Man’s Fight.’8 When Liz Ahern married Mr Wallace and settled in Broken Hill, she wrote on the Marriage Register, occupation, ‘Socialist Agitator.’9 On November 2 1908, she addressed a Trades Union gathering on ‘The War of the Classes.’

In 1915, the Hotel Club and Restaurant Employees Union, comprised mostly of female members, called upon the AMA to support their actions for a new agreement. The Licensed Victualers and Race Club meeting was boycotted. The AMA stepped in to help the women sustain a long fight during which nine establishments were ‘brought to heel’. The women refused to return to work with ‘scabs’ until all free labourers were dismissed. This established solidarity between the AMA and HCREU which was evident in the ensuing anti-conscription industrial actions of 1916.

- n.a. Silver Age, 26 August 1892.

- n.a. Barrier Miner, 12 August, 1892

- Hales, ‘Smiler’ (1890) The wanderings of a simple child or sketches of life in the back country. Sydney:Gibbs, Shallard & Co. p.140

- Hales, ibid.p.150

- Kearns, R.H.B (1982) Broken Hill— A pictorial history, Adelaide: Investigator Press.p.154

- Barrier Miner, 4 July 1892

- Silver Age, 26 August 1892.

- Bloodworth, S. (1996) Rebel Women: Women and Class in Broken Hill, 1889-1917 Melbourne: La Trobe University.

- Bloodworth, S. Ibid.